Matthew Chapter Two

The

Nativity of Christ The

Nativity of Christ & Death of Herod the Great by Kurt Simmons, JD |

[Editor's note: We are writing a commentary on the book of Matthew. The following is a draft of chapter two. We believe it provides the clearest, most concise evidence of Chris's December 25th birth unearthed to date. Although the whole chapter can and should be read with profit, for comments specifically bearing upon the date of Christ's birth and the death of Herod, see vv. 9-23.]

Having established Jesus’ genealogy and claim to the Davidic

throne in the preceding chapter, Matthew provides the historical

details of Christ’s birth, punctuating the narrative with

accounts of prophetic fulfillment.

1 – Now when Jesus was born

Matthew opens his discussion of

Nativity with the arrival of the Magi. The Greek term here is

gennhqentoj,

“having been born,” perfect tense, showing completed action in

the past. Thus, Jesus was already born when the wise men

arrived. The question is how long after his birth until they

arrived? It is often assumed that the wise men found Christ in

the manger at Bethlehem the night of his nativity. But this is

contradicted by v. 11, which says they found him in a

house, not manger.

Hence, the wise men clearly did not arrive the night of Jesus’

birth. At the other extreme, based upon v. 16, it is sometimes

supposed the wise men arrived as much as

two years after Jesus’

birth. However, this cannot be reconciled with Luke, on the one

hand, who places Jesus’ thirtieth birthday in A.D. 29 (Lk. 3:1,

23), making his birth occur in 2 B.C., or Josephus, on the other

hand, who places Herod’s death in 1 B.C. Since Jesus was born

while Herod was still alive and there were not two years between

his birth and Herod’s death, the Magi could not have arrived two

years after Jesus’ birth. As we shall see, there were in fact

only several months between Jesus’ winter birth and Herod’s

death shortly before Passover the following spring.

in Bethlehem of Judaea

Bethlehem was prophesied to be the birth place of the Messiah (see v. 5). Bethlehem means “house of bread,” perhaps in veiled prophecy of the nativity of him who is the “bread of life” (Jn. 6:48). It was anciently known as Ephrath (Gen. 35:16; 48:7; Ps. 132:6), and was the place where Rachel died and was buried (Gen. 35:19; 48:7); it was also where the story of Ruth took place, and was the home and the city of David (I Sam. 16:1, 4; Jn. 7:42). However, Bethlehem was not the home of Joseph or Mary. Luke informs us that the couple made their home instead in Nazareth of Galilee (Lk. 1:26; 2:39). According to Luke, it was in obedience to the decree of Caesar Augustus “that all the world be taxed” that Joseph travelled to Bethlehem to be taxed with Mary his espoused wife “being great with child” (Lk. 2:1-7). Luke tells us further, that this taxing was “first made when Cyrenius was governor of Syria” (Lk. 2:2). The word translated tax in these passages is from the Greek apografesqai, which means to “write out” “enter in a list” or “register,” and can therefore be translated either as “census” or “registration.” When translated as census, it is usually associated with a tax. The difficulty here is that the tax of Cyrenius did not occur until A.D. 6, following the banishment of Herod’s son, Archelaus, when it provoked the sedition of Judas of Galilee.

“Now Cyrenius, a Roman senator, and one who had gone through other magistracies, and had passed through them till he had been consul, and one who, on other accounts, was of great dignity, came at this time into Syria, with a few others, being sent by Caesar to be a judge of that nation, and to take an account of their substance. Coponius also, a man of the equestrian order, was sent together with him, to have the supreme power over the Jews. Moreover, Cyrenius came himself into Judea, which was now added to the province of Syria, to take an account of their substance, and to dispose of Archelaus's money; but the Jews, although at the beginning they took the report of a taxation heinously, yet did they leave off any further opposition to it, by the persuasion of Joazar, who was the son of Boethus, and high priest; so they, being over-persuaded by Joazar's words, gave an account of their estates, without any dispute about it. Yet was there one Judas, a Gaulonite, of a city whose name was Gamala, who, taking with him Sadduc, a Pharisee, became zealous to draw them to a revolt, who both said that this taxation was no better than an introduction to slavery, and exhorted the nation to assert their liberty.”[1]

But as these events were several years too late, and as Luke knew of the revolt of Judas of Galilee (Acts 5:37), the better view is that the apografesqai which brought Joseph and Mary to Bethlehem was not a census for taxation, but a registration. Josephus reports just such a registration that occurred the year Herod died, when Saturninus was still president of Syria, before he was succeeded by Quintilius Varus, in which all the people of the Jews gave an oath of their good will and allegiance to Caesar:

“These are those that are called the sect of the Pharisees, who

were in a capacity of greatly opposing kings. A cunning sect

they were, and soon elevated to a pitch of open fighting and

doing mischief. Accordingly, when all the people of the Jews

gave assurance of their good-will to Caesar, and to the king’s

government, these very men did not swear, being above six

thousand; and when the king imposed a fine upon them, Pheroras’s

wife paid their fine for them.”[2]

We believe this is the registration referred to by Luke. The term translated “governor” in Lk. 2:2, is hegemoneuontoj, and is the root of our English word hegemon, and can signify either a governor (legatus or praeses), as it is usually translated, but also an imperial commissioner or procurator (quaestor). The same word is used in this later sense of Pilate in Lk. 3:1. Given that the term might apply equally to either of these important offices, it is likely that Cyrenius first served as hegemon associated with Saturninus in the government of Syria, and a second time at the taxation, which led to the revolt of Judas of Galilee. This seems to be corroborated by Tertullian, who wrote in the second century that the registration “had been taken in Judea by Sententius Saturninus.”[3] The registration was likely prompted by Augustus being honored by the Roman senate, the equestrian order, and the whole people of Rome, with the title Pater Patriae (Father of the Country). The title was given to Augustus February 5, during his thirteenth consulship, which answers to 2 B.C. and coincides with Saturninus’ presidency of Syria.[4] Paulus Orosius describes the whole affair in reference to Luke 2:2 as follows:

“Augustus ordered that a census be taken of each province everywhere and that all men be enrolled…This is the earliest and most famous public acknowledgment which marked Caesar as the first of all men and the Romans as lords of the world, a published list of all men entered individually…This first and greatest census was taken, since in this one name of Caesar all the peoples of the great nations took oath, and at the same time, through the participation in the census, were made a part of one society.”[5]

|

in the days of Herod the king, This is Herod the Great, as distinguished from Herod Antipas, tetrarch of Galilee, son of Herod by his wife Malthace, and Herod Philip, tetrarch of Iturea and Trachonitas, Herod’s son by Mariamne (Matt. 14:1; Lk. 3:1). Regarding Herod Archelaus, see comments at v. 22. Herod the Great must also to be distinguished from Herod Agrippa I (Acts 12:1), king of Judea and Samaria, grandson of Herod the Great by Aristobulus, and Herod Agrippa II, great grandson of Herod the Great, who was king of Chalcis, his sister, Bernice, being queen (Act 25:13). |

|

Herod the Tetrarch ruled Galilee during the Lord’s

ministry; it was he that beheaded John the Baptist and to him

that Pilate sent Jesus at his trial (Lk. 23:6, 7). After the

death of Tiberius, Gaius Caligula made Herod Agrippa I king of

Ituria, Trachonitis, and Abilene, which had been the tetrarchies

of Philip and Lysanias (Lk. 3:1).[6] Agrippa I

was present in Rome when Caligula was murdered and helped bring

Claudius Caesar to power. Claudius rewarded Agrippa by expanding

his dominions to include all the lands previously ruled by Herod

the Great (Judea and Samaria), which had been divided amongst

his sons.[7] Agrippa I

persecuted the church briefly, putting to death James the

brother of John, and sought also to slay Peter (Acts 12:1-19).

The death of Agrippa I is recorded by Josephus, whose account

accords perfectly with Luke’s record in Acts (Acts 12:20-25).[8] Herod

Agrippa II was but a youth when his father died and was deemed

too young to manage his kingdom. Hence, Claudius returned Judea

to a province, and made Agrippa II king of his uncle’s dominions

(Chalcis) when he was dead. Agrippa’s sister, Bernice, was queen

with her brother, being the widow of her uncle, her father’s

brother (Acts 25:13).[9] Agrippa II

assisted Vespasian in the Jewish war and served Titus at the

destruction of Jerusalem.[10] Following

the war, he went to Rome where he was given the rank of praetor.

Bernice became the lover of Titus, cohabiting with him in the

palace under an apparent expectation of marriage. However, the

Roman people were scandalized, and Titus was forced finally to

send her away, only to have her return again when he was

emperor.[11] Thus far

the posterity of Herod the Great and the Herods mentioned in the

gospels and Acts.

Herod the Great first came to

power by his father, an Idumean named Antipater, who had secured

the government for Hyrcanus II, but at the cost of the nation’s

independence. Beginning with the Babylonian captivity in 586

B.C., the Jewish nation was under foreign domination. It

regained its independence briefly (142 B.C.) under the period of

the Greeks,[12] but

through intestine disputes soon found itself under the power of

Rome. The government of the Jews had been combined in the high

priest by Aristobulus, son of John Hyrcanus, who was the first

of the priestly line to done a crown. Aristobulus was followed

in the government by Alexander, who left two sons: Hyrcanus II,

the elder, and Aristobulus II, the younger. The government came

first to Alexander’s widow, queen Alexandra, who made Hyrcanus

II high priest because he was the elder. But when the queen

died, Aristobulus made war against his brother. In the contests

that followed, the parties each sent ambassadors to Pompey the

Great, seeking his favor and military support. The ambassador

for Hyrcanus was Antipater, Herod’s father. When the parties had

submitted their causes to Pompey, Aristobulus fled to Jerusalem,

shutting up the city against Pompey before he gave any decision.

Aristobulus later capitulated and surrendered to Pompey, but the

members of his party would not accept his capitulation or

surrender the city. Angered, Pompey besieged the city, taking it

after a siege of five months (63 B.C.). Pompey confirmed

Hyrcanus in the high priesthood, but joined the country to the

province of Syria under a president, ending national

independence. Though Hyrcanus was high priest, the country was

managed by Antipater.

Hyrcanus and Antipater thus

continued in the government until the civil war that ended the

Roman republic (49 B.C.) and brought Julius Caesar to supreme

power. Following his defeat at Pharsalus (48 B.C.), Pompey fled

to Egypt. Caesar pursued Pompey there, only to find when he

arrived that Pompey had been assassinated by the Egyptians.

Caesar also found king Ptolemy XIII making war against his

sister and coregent, Cleopatra, whom he had expelled from the

throne shortly before. Egypt was a protectorate of Rome; Caesar

was consul that year and attempted to have the parties settle

their dispute before him in process of law, rather than by armed

force. Thinking it unseemly for a king to submit the contest to

Caesar’s arbitrage, Ptolemy attacked Caesar’s forces with the

royal army. In the war that followed, Antipater came to Caesar’s

assistance with numerous recruits, even turning a battle that

helped save the day. Victorious, Caesar settled the government

of Egypt on Cleopatra as queen, then came to Syria the following

summer and settled the government there (47 B.C.). He rewarded

Antipater with the procuratorship of Judea; Antipater in turn

made his son, Phasaelus, governor of Jerusalem; Herod was given

charge of Galilee being twenty-five years of age.[13] This is

important because it dates Herod’s birth to the summer of 72

B.C., allowing us to date his death shortly before Passover at

age 70 to 1 B.C.

After the death of Julius Caesar (44 B.C.) and the defeat of Cassius and Brutus (42 B.C.), Marc Antony marched into Asia, then Syria where he met Cleopatra and fell in love (41 B.C.). At the same time, Herod gained Antony’s friendship with large gifts of money, and Antony made Herod and his brother Phasaeslus tetrarchs. But in the second year, the Parthians invaded the land, took Hyrcanus and Phasaeslus captive, and installed Antigonus, the son of Aristobulus, as king. Herod fled to Rome, where Antony and Octavian Caesar caused the Roman senate to make Herod king. Josephus places this in the one hundred eighty-fourth Olympiad in the consulship of Calvinus and Pollio (40 B.C.),[14] but Appian dates it to 39 B.C.[15] Herod then returned to Palestine and, with the help of the Roman general Sossius, after three years finally captured Jerusalem. Herod procured the execution of Antigonus by Marc Antony shortly thereafter. Josephus dates this to the one hundred eighty-fifth Olympiad during the consulship of Agrippa and Gallus (37 B.C.), but also dates it to exactly 27 years from Jerusalem’s fall to Pompey, which translates to 36 B.C.[16] This latter date seems to be corroborated by Dio Cassius, who says the Romans “accomplished nothing worthy of note” in the area in 37 B.C.[17] It is also consistent with Josephus’ statement that the death of Antigonus concluded the Hysmonean dynasty one hundred twenty-six years after it was set up in 162 B.C., having held the high priesthood for three years and three months.[18] Three years and three months from 36 B.C. would place the Parthian capture of Hyrcanus to the summer, and Herod’s appointment as king in Rome to the winter, of 39 B.C. A final note pointing to Herod’s receiving the kingdom in late 39 B.C. is the following statement of Josephus:

“The number of high priests from the days of Herod until the day

when Titus took the temple and the city, and burnt them, were in

all twenty-eight; and the time also that belonged to them was a

hundred and seven years.”[19]

Titus captured the temple and

destroyed Jerusalem in August, A.D. 70. Reckoning backward one

hundred seven years from this date will bring us to 38 B.C.,

which would have been the first regnal year of Herod following

his appointment as king in Rome in winter 39 B.C. Thus, began

the reign of Herod the Great. He died in 1 B.C. several months

after the birth of Christ, having reigned 37 years from being

declared king by the Romans, but 34 years from the capture of

Jerusalem and death of Antigonus. (See comments at v. 22.)

|

behold, there came wise men from the east to Jerusalem, Herodotus gives the name of the tribes of the Medes as Busae, Parataceni, Struchates, Arizanti, Budii, and the Magi.[20] The term rendered “wise men” here is from the Greek magio, or “Magi,” and is derived from the tribe of the Medes that carries the same name. |

This tribe was

occupied in interpreting dreams, astrology, and the religious

rites of their people, similar to the Chaldeans among the

Babylonians, and the tribe of Levi among the Jews.It is likely that it is to men of this tribe the second chapter

of Daniel refers when it mentions the wise men, astrologers,

magicians (LXX,

magwn),

Chaldeans, and soothsayers of Nebuchadnezzar’s court who could

not interpret the king’s dream (Dan. 2:27).

This may be the link that explains why these men came

from the east seeking the Christ child.

Beginning with verse four of

Daniel chapter two, following the word “Syriack,” the Hebrew

suddenly stops and the book is written in Aramaic through the

end of chapter seven. Aramaic was the international language of

diplomacy and commerce of the day.[21] These

chapters were recorded in Aramaic that they might be known and

read by the Gentile peoples of the Babylonian and Mede-Persian

empires, during whose days they were composed. God wrought many

mighty works in the Babylonian and Mede-Persian courts, which

are recorded in these chapters, including the events surrounding

Nebuchadnezzar’s dream (Dan. 2), the rescue of the three young

men (Dan. 3), the king’s madness and conversion (Dan. 4), the

hand that appeared on the wall during Belshazzar’s feast (Dan.

5), and God’s rescue of Daniel from the lion’s den (Dan. 6).

Moreover, in addition to the miraculous circumstances attending

Nebuchadnezzar’s dream, the prophecy of Daniel two, and its

companion prophecy in chapter seven, foretold the succession of

world empires until the kingdom of God, and therefore served as

timelines unto the birth of Christ. Given the mighty works of

God in the royal court and their publication in Aramaic, we may

imagine that there were many proselytes among the nations,

including ancestors of the Magi here, who learned of Christ’s

coming from the writings of Daniel, and were watching for his

birth.

2 – Saying, Where is he that is born King of the Jews? For we

have seen his star

Star, comets, and celestial bodies are commonly associated with

great revolutions in world affairs, and are part of the imagery

used by the prophets to describe cataclysmic judgments and the

rise and fall of earthly powers (Isa. 13:10; 34:1-4; Lk. 21:25;

Rev. 8:10, 12; 9:1). Two passages are traditionally assigned as

predicting that the advent of the Messiah would be attended by a

star. The first is Balaam’s prophecy in Num. 24:17: “A

Star shall rise out of Jacob and a Sceptre shall rise out of

Israel.” The other passage is Isa. 60:3:

“And the Gentiles shall

come to thy light, and kings to the brightness of thy rising.”

Various attempts have been made down through the centuries to

identify the star that led the Magi to Christ by appeal to

natural phenomena and astrological occurrences, typically the

conjunction or massing of planets.[22] Such

attempts proceed upon the assumption that the star was a

regularly occurring phenomenon, repeated at set intervals, which

may be identified by mathematical formula in the same way men

are able to predict lunar and solar eclipses. Against this,

however, it may be urged that the notion the star seen by the

Magi was a conjunction or massing of planets is contradicted by

the plain language of scripture.

By all accounts, the Magi were expert astronomers who probably came

from the area of Media, and would have been thoroughly familiar

with the movements of celestial bodies and the conjunction of

planets. Matthew is very clear that the Magi referred to the

phenomenon that drew them to Jerusalem as a “star.” The

Greek term Matthew employed is "astera" (singular). The term for multiple stars is the plural "asterej" (Rev. 6:13). The Greek phrase for planet is " asthr planhthj" (“a wandering star”) and the plural is “asterej planetej” (Jude 13). If the Magi saw one or more planetary

conjunctions, we would expect them to use language reasonably

calculated to communicate as much. The fact that they described

a single star, and not a planet, or series of conjunctions of

stars or planets, refutes all such notions. Instead, the better

view is that the star

was

a supernatural phenomenon, unlike anything that has occurred

before or since, whose meaning and significance was made known

to the Magi by divine revelation.

in the east

Magi

from the east (apo

anatolwn)

saw the star in the east

(en th anatolh).

This probably signifies the region of Media, then part of the

kingdom of Parthia. From v. 16, we learn that the star

originally appeared two years before. Thus, the arrival of the

Magi at Jerusalem came at the end of a pilgrimage begun two

years before, during which the star seems to have appeared

intermittently at irregular intervals along the way. We learn

from v. 12 that God communicated with the Magi by dreams. Since

the appearance of a star could not, without more, tell the Magi

a king was born or what nation he would rule, we may assume the

meaning of the star was communicated to the Magi by divine

revelation.

and are come to worship him.

They have not come merely to

honor a new-born king, but to worship him, signifying they

understood somewhat the divine nature of the Christ-child. The

word rendered “worship” is from the Greek

proskunew,

“to prostrate oneself in

homage, do reverence to, adore.” Since this would not be the

kind of honor normally shown to a human king of a foreign

nation, this attests to the fact that the Magi were almost

certainly religious proselytes and worshippers of the Lord, like

the Medes, Elamites, and Parthians who came to Jerusalem to

worship at Pentecost following Christ’s ascension (Acts 2:9).

|

3 – When Herod the king had heard these things, Herod the king is set in apposition to him that was born King, whom the Magi had come to worship. Josephus reports that Herod ruled by terror, intimidation, and secret police. It is probably Herod’s spies and informants that carried word of the Magi’s arrival to his ears. Josephus gives the following description, which was typical of Herod’s reign: |

|

“At which time Herod released to his subjects the third part of

their taxes, under pretense indeed of relieving them after the

dearth they had had, but the main reason was, to recover their

good-will, which he now wanted; for they were uneasy at him,

because of the innovations he had introduced in their practices

of the dissolution of their religion, and of the disuse of their

own customs, and the people everywhere talked against him, like

those that were still more provoked and disturbed at his

procedure; against which discontents he greatly guarded himself,

and took away the opportunities they might have to disturb him,

and enjoined them to be always at work; nor did he permit the

citizens either to meet together, or to walk, or eat together,

but watched everything they did, and when they were caught, they

were severely punished; and many there were who were brought to

the citadel Hyrcania, both openly and secretly, and were there

put to death; and there were spies set everywhere, both in the

city and in the roads, who watched those that met together; nay,

it is reported that he did not himself neglect this part of

caution, but that he would oftentimes himself take the habit of

a private man, and mix among the multitude in the night-time,

and make trial what opinion they had of his government; and as

for those that could be no way reduced to acquiesce under his

scheme of government, he persecuted them all manner of ways; but

for the rest of the multitude, he required that they should be

obliged to take an oath of fidelity to him, and at the same time

compelled them to swear that they would bear him good-will, and

continue certainly so to do, in his management of the

government; and indeed a great part of them, either to please

him, or out of fear of him, yielded to what he required of them;

but for such as were of a more open and generous disposition,

and had indignation at the force he used to them, he by one

means or other made away with them.”[23]

he was troubled, and all Jerusalem with him.

Herod was troubled because he was

dying, and his thoughts were for the perpetuation of his kingdom

by settling succession upon his sons, which was threatened by

word of the new-born King.

By the time the Magi arrived,

Herod was in the final weeks of his life. Antipater, Herod’s son

by Doris, had been tried for treason before Quintilius Varus,

who succeeded Saturninus as president of Syria. Condemned, Herod

feared to send Antipater to Caesar for punishment, lest he

somehow escape. Antipater was thus held in the palace prison at

Jericho, and Herod sent letters and ambassadors to Augustus

Caesar to accuse Antipater and learn Caesar’s pleasure

concerning his son. However, while waiting for word from Caesar,

Herod fell gravely ill. This was now about the seventieth year

of his life, and he despaired of recovery. Herod thus made his

will, temporarily settling the kingdom upon his youngest son,

Herod Antipater. Facing death and knowing that he was hated by

the Jews, Josephus reports that Herod “grew fierce, and indulged

the bitterest anger upon all occasions,” and more especially

because of a sedition that now broke out.

Herod had placed a large Roman

eagle above the gate of the temple, which the Jews considered an

affront to their religion. Taking the opportunity of Herod’s

impending death, several prominent rabbis moved the young men to

cut the eagle down. When rumor came that Herod was dead, the

young men made an assault on the temple in broad daylight, and

cut down the eagle. However, the soldiers came upon them

suddenly, and when they had been captured, Herod had them sent

to Jericho, where the leaders were burned alive. Josephus

reports that the night of the rabbis’ execution there was an

eclipse of the moon.[24] This

lunar eclipse is important for dating Herod’s death. For many

years, it was supposed to be the partial lunar eclipse of March

13, 4 B.C. But this has now been thoroughly refuted, and leading

scholarship agrees that this was the full lunar eclipse of

January 10, 1 B.C.

[25]

Herod’s final illness now grew

worse; he thus travelled beyond the Jordon River to bathe in

mineral springs as a curative for his disease. However, when

this failed to improve his health, Herod returned to Jericho,

dying shortly thereafter, never to return to Jerusalem again.

The arrival of the Magi would therefore have occurred about this

time, shortly after the execution of the Rabbis, but before

Herod travelled beyond the Jordan, probably toward the middle of

February, 1 B.C.[26] (See

additional comments at v. 11.)

4 – And when he had gathered all the chief priests and scribes

of the people together, he demanded of them where Christ should

be born.

The Magi came seeking an

infant-King; Herod correctly interprets this in reference to the

promised Christ. Herod’s response indicates that the Magi were

well received and their story credited among the leaders of the

Jews. That they were also brought into the king’s presence (v.

7) bespeaks something of the Magi’s social standing: these were

no mean strangers, but men of sufficient wealth and standing to

find an audience with the king. Like the angelic host that

appeared to the shepherds as told by Luke (Lk. 2:9-14), the star

and arrival of the Magi are heavenly signs testifying that

heaven has come down to earth to reclaim the fallen race of

Adam.

5, 6 – And they said unto him, In Bethlehem of Judaea: for thus

it is written by the prophet, And thou Bethlehem, in the land of

Juda, art not the least among the princes of Juda: for out of

thee shall come a Governor, that shall rule my people Israel.

The chief priests and scribes

cite Micah 5:2 to indicate where Christ should be born. There

are several differences between their paraphrase and the Hebrew

as we possess it. “Land of Judah” replaces “Ephratah,” and

“among the princes” replaces “among the thousands.” The scribes

likely paraphrased it this way for Herod as an incident of

casual speech in answer to his question rather than a

word-for-word quotation. However, it is worth our noting that

Micah’s “thousands” does not refer to the cities and villages of

Judah, but to the captains

of thousands. Moses had divided the people into rulers of

thousands, hundreds, fifties, and tens at the suggestion of his

father-in-law, Jethro (Ex. 18:25). Thus, Micah’s meaning seems

to be that, although comparatively small, from among the

captains of thousands who ruled the people, one would arise from

Bethlehem who would be ruler over all. The marginal reading for

the word “rule” is “feed,” and shows that Christ would not

merely govern, but is the Great Shepherd who would nourish his

people and lead them into paths of eternal life. Micah 5:2 is

also among the Old Testament texts, which show Christ was

divine, for the prophet says that Israel’s ruler would be one

whose “goings forth have been from old,

from everlasting” (cf.

Jn. 1:1; 8:58). It is

likely that the chief priests and scribes did not understand the

meaning of this and that Christ was God incarnate, and therefore

omitted its mention to Herod.

7 – Then Herod, when he had privily called the wise men,

inquired of them diligently what time the star appeared.

Herod has already determined to

murder the Christ-child, and therefore confers secretly with the

Magi, lest word of the conference becoming known alert the holy

family and they conceal themselves from the Magi. The Magi are

thus made Herod’s unwitting agents to catch and destroy the

infant-King. Herod examines the Magi diligently to learn when

the star first appeared, so that he may determine the range of

the child’s age. Herod’s purpose is to get sufficient

information to correctly identify the one he purposes to murder.

8 - And he sent them to Bethlehem, and said, Go and search

diligently for the young child; and when ye have found him,

bring me word again, that I may come and worship him also.

Having plied the Magi for all the

information he could obtain, Herod now sends them to Bethlehem,

where it is supposed the child resides. Herod feigns he is a

religious man, and instructs the Magi to return to him again,

when they have found the child, that he too might pay him

homage. Based upon the time the star first appeared (v. 16), it

is sometimes supposed that Christ was as much as two years old

when the Magi arrived, and Herod’s use of the phrase “young

child” certainly may have contemplated as much. But the word

itself (paidiov)

does not give proof of the child’s age, for Luke uses the same

term for the babe at eight days old when he was circumcised (Lk.

2:21), and again at his presentment in the temple at forty days

of age (Lk. 2:27). Indeed, we believe the record will show that

Christ was less than two months old when the Magi found him.

|

9, 10 – When they had heard the king, they departed; and, lo,

the star, which they saw in the east, went before them, till it

came and stood over where the young child was. When they saw the

star they rejoiced with exceeding great joy.

We here find evidence that the

star is a supernatural phenomenon, for it appears again after

some while being unseen, and goes before the Magi, leading them

to the Christ-child. Surely, to urge this was a mere conjunction

of planets is more than the text will bear. |

Bethlehem is only about ten miles

distant from Jerusalem. Since the Magi were specifically

directed there by Herod, we should not imagine this is where the

star led them. Rather, we learn from Luke that, after the

forty-day period of ritual impurity following birth of a male

child, the holy family travelled to Jerusalem, where they made

the necessary offerings for Mary and her first-born son (Ex.

13:2, 12, 13; Lev. 12:2-4, 8), then returned to their home in

Nazareth (Lk. 2:22-24, 39). There are only two options when

these events could have occurred: Before the flight to Egypt, or

afterward, when the holy family returned from exile. The

language of Luke gives every indication that the presentation at

the temple followed immediately upon conclusion of Mary’s period

of ritual impurity. At eight days of age, Jesus was circumcised

(Lk. 2:21), then at forty-days he was presented at the temple

(Lk. 2:22-24). There is no suggestion of any postponement. In

fact, the possibility that the presentation was postponed until

the return from Egypt is expressly contradicted by Matthew, who

says that Joseph, learning Archelaus reigned in Judea in place

of his father, “was afraid to go thither,” and being warned in a

dream, Joseph “turned aside” into Galilee, avoiding Judea

entirely (Matt. 2:22). Thus, there would have been no

possibility of the presentation to occur following the exile.

Since Bethlehem is so near to Jerusalem, and the Magi were

directed there by Herod in any event, and therefore would not

need the star to direct them there, the better view is that the

star was interposed by heaven to direct the Magi to where the

child had removed, viz.,

to Nazareth, where the holy family had returned about forty-five

days after Jesus’ birth.

11 – And when they were come into the house, they saw the young

child with Mary his mother,

We here find confirmation that

the holy family was already returned to Nazareth, for the Magi

found the mother and child in the family house (oikiav),

and not at an inn or the cave at Bethlehem.

and fell down, and worshipped him:

We my note the complete absence

of vernation or homage of any sort to Mary, though present with

the babe. Christ was God incarnate, and therefore the proper

object of worship, which none other can claim. When Cornelius

fell down upon his knees before Peter, the apostle strictly

forbade it, saying, “I myself am also a man” (Acts 10:25, 26).

When the Lyconians sought to offer sacrifice to Paul and

Barnabas, they rent their clothes and restrained the people,

saying, “we also are men of like passions with you, and preach

unto you that ye should turn from these vanities unto the living

God” (Acts 14:15). Yea, even angels forbade men to adore them

(Rev. 19:10; 22:9). If it was forbidden to give homage to Mary

and the person of the apostles, how much more must we imagine it

to be unlawful to render homage to statues and images of them,

or the relics of supposed saints?

and when they had opened their treasures, they presented unto

him gifts; gold, and frankincense, and myrrh.

The presentation of gifts

anticipates the conversion of the Gentiles foretold by the

Psalmist: “The kings of

Tarshish and of the isles shall bring presents: the kings of

Sheba and Seba shall offer gifts. Yea, all kings shall fall down

before him: all nations shall serve him” (Ps. 72:10).

“And the Gentiles shall

come to thy light, and kings to the brightness of thy

risings…the abundance of the sea shall be converted unto thee,

and the forces of the Gentiles shall come unto thee…all they

from Sheba shall come: they shall bring gold and incense; and

they shall shew forth the praises of the Lord” (Isa.

60:3-6). “And I will shake

all nations, and the desire of all nations shall come: and I

will fill this house with glory, saith the Lord of hosts”

(Hag. 2:7). It is traditional to interpret the three gifts of

gold, frankincense, and myrrh as signifying there were three

Magi, but the evidence is inconclusive and it cannot be

certainly known.[27] Gold,

frankincense, and myrrh were precious commodities, but are also

thought to have symbolic value: gold for Christ’s

kingship; frankincense

for his priestly office;

myrrh prefiguring his

anointing and death.

12 – And being warned of God in a dream that they should not

return to Herod, they departed into their own country another

way.

That God deigned to communicate

with the Magi by dream suggests that their pilgrimage to find

the Christ-child was by divine intimation and direction from the

very start, and not by the power of human interpretation

attached to the appearing of the star. Rather than representing

different races and peoples, the Magi have a common country, to

which they now return. It will be thirty years before the Savior

begins his ministry. Meanwhile the Magi, having returned home,

can tell God’s mighty works among their countrymen and help

prepare them for the gospel of Jesus Christ.

|

13 – And when they were departed, behold, the angel of the Lord

appeareth to Joseph in a dream, saying, Arise, and take the

young child and his mother, and flee into Egypt, and be thou

there until I bring thee word: for Herod will seek the young

child to destroy him.

Although no longer in Bethlehem,

the Roman registration would have just concluded, if it was not

still under way. Herod could easily have obtained from

Quintilius Varus records of the registrants, and thus trace the

holy family back to Nazareth where they made their home. Herod’s

kingdom and jurisdiction included Galilee; hence it was not safe

for the holy family to remain in the land. The angel thus

directs Joseph to flee to Egypt, which had been made a Roman

province since the death of Antony and Cleopatra. |

|

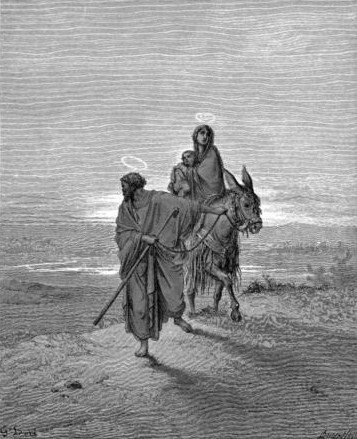

14, 15 – When he arose, he took the young child and his mother

by night, and departed into Egypt: and was there until the death

of Herod: that it might be fulfilled which was spoken of the

Lord by the prophet, saying, Out of Egypt have I called my son.

The period between their flight to Egypt and Herod’s death was probably not more than about two months, though they did not return until the government was settled upon Archelaus (Matt. 2:19-23). Based upon the offering at the temple of two turtle doves (Lk. 2:24), it is commonly supposed that Joseph was a poor man. It seems unlikely that Joseph could well afford to support the family in a strange land; the gifts of the Magi thus become heaven’s provision for the family’s flight. There was a large Jewish population in Egypt and Alexandria, which had a large portion of the city assigned to them and were declared its citizens by Julius Caesar.[28] It may be that it was to Alexandria that Joseph, Mary, and baby Jesus had recourse. The prophecy cited by Matthew is from Hosea 11:1:

“When Israel was a child, then I loved him, and called my son

out of Egypt.”

The basic thought or supposition

is that what occurred to Israel the nation was at various points

a prophetic type that found further fulfillment in Christ. The

prophecies and events cited by Matthew (Isa. 7:14; Hos. 11:1;

Jer. 31:15-17) sometimes bear an obvious reference to Christ,

sometimes not. But as no prophecy of scripture is of private

interpretation (II Pet. 1:20, 21), Matthew must be understood as

speaking by authority of the Holy Ghost and not his own

volition, so that what he affirms was being fulfilled in Christ

had been foreordained by God, who set them as ancient landmarks

to mark off the identity of the Messiah.

16 – Then Herod, when he saw that he was mocked of the wise men,

was exceeding wroth, and sent forth, and slew all the children

that were in Bethlehem, and in all the coasts thereof, from two

years old and under, according to the time which he had

diligently inquired of the wise men.

It has been alleged at various times that the Slaughter of the Innocents never occurred, but stands as a piece of anti-Herodian fiction.[29] The chief objection to the verity of Matthew’s account is that it is not mentioned by Josephus, but is the only record we have of the events described. Also, the crime itself seems too barbarous to be believed. But these objections are without merit. There are any number of reasons Josephus might neglect to record the Slaughter of the Innocents, not the least of which being that his primary source for Herod’s reign was Nicolas of Damascus, who was Herod’s friend and personal historian, and was known to misrepresent facts to gratify Herod. Josephus says of Nicolas:

“He wrote in Herod’s lifetime, and under his reign, and so as to please him, and as a servant to him, touching upon nothing but what tended to his glory, and openly excusing many of his notorious crimes and very diligently concealing them.”

[30]Given that Nicolas of Damascus actively concealed the crimes of Herod in his histories, we may assume that he suppressed the Slaughter of the Innocents in deference to his friend, and that Josephus fails to report it because he did not find it in Nicolas’ histories of Herod’s reign. Josephus may also have omitted mention of Herod’s crime, to avoid insulting the Roman people, whose senate had issued the identical decree at the time Augustus was born. Suetonius reports

“A few months before August was born a portent was generally

observed at Rome, which gave warning that nature was pregnant

with a king for the Roman people: thereupon the senate in

consternation decreed that no male child born that year should

be reared.”[31]

The ancient world was steeped in

infanticide, and to expose unwanted infants an accepted norm of

life among the pagan world. The Roman senate being on record as

having ordered the exposure of all male children born in the

compass of an entire year, we can imagine Josephus’ reluctance

to mention the similar crime of Herod. How could Josephus

incriminate Herod for the Slaughter of the Innocents without

also incriminating the Roman senate? His silence here therefore

should not surprise us. That Herod was fully capable of such a

crime is only too apparent. Herod slew three of his sons, his

mother-in-law, his wife’s brother, and his wife; to say nothing

of the countless political opponents he slew, and anonymous

others secreted away to the fortress Hyrcania where they

miserably perished. One of Herod’s last acts was to order that

the elders of the Jews be shut up in the Hippodrome at Jericho

and, upon Herod’s death, be slain, that there might be a general

mourning at his passing.[32]

Clearly, a man of demonstrated ability to slay without mercy his

own sons and family members, and to order the indiscriminate

murder of the nation’s nobility, is fully capable of destroying

the nameless children of others.

But as to the charge that Matthew is the only account we possess of the slaughter of Bethlehem’s babes, here we must beg to differ. St. John makes obvious reference to Herod’s attempt to destroy the Christ-child in his apocalypse:

“And there appeared a great wonder in heaven; a woman clothed

with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a

crown of twelve stars: and she being with child cried to be

delivered. And there appeared another wonder in heaven; and

behold a great red dragon, having seven head and ten horns, and

seven crowns upon his heads. And his tail drew the third part of

the stars of heaven, and did cast them to the earth: and the

dragon stood before the woman which was ready to be delivered,

for to devour her child as soon as it was born.” Rev. 12:1-4

Here is unquestionable reference

to Herod’s attempt to slay the Christ-child. The woman is not

Mary, but Zion, the virgin of Israel, the Old Testament

congregation of God’s faithful groaning in travail to be

delivered from sin and death, and from their earthly enemies.

She is pregnant with the promise of the Savior. The dragon is

Leviathan, Rome, the world civil power opposing God and

oppressing his people. Its seven heads and ten horns stand for

the political subdivisions of the Empire: the ten horns are the

ten senatorial provinces created by Augustus in 27 B.C., which

became identifying features of the Empire and its divided rule,

but very likely stand for the whole of its provinces. The seven

heads represent the imperial Caesars from Julius until Galba,

who came to power shortly after the apocalypse was written (Rev.

17:10). Herod was a client king of Rome and his acts are

attributed to the dragon. Thus, although Mark and Luke do not

mention the Slaughter of the Innocents, John does and thus

becomes a witness to the verity of the Matthew’s record.

Finally, there is the testimony of Macrobius. Macrobius wrote an encyclopedic account of Roman culture entitled the Saturnalia in which he records the legends and lore of the holidays marking the Roman calendar. In book two, Macrobius records some of the witting sayings of Augustus Caesar, and there reports:

“On hearing that the son of Herod, king of the Jews, had been

slain when Herod ordered that all boys in Syria under the age of

two be killed, Augustus said, ‘It’s better to be Herod’s pig

than his son.’”[33]

The authenticity of Macrobius’

report is not disputed. However, it is sometimes read to include

Antipater among those who perished in the Slaughter of the

Innocents, which obviously would be incorrect. However,

Macrobius may merely have intended to indicate that Antipater

was executed at the same time the Slaughter of the Innocents was

being carried out. We need not enter into a discussion which is

correct, for by either reading the death of Antipater and

Slaughter of the Innocents were contemporaneous events. This

means that by ascertaining when Antipater died we may also learn

when the Massacre of the Innocents occurred.

|

17, 18 – Then was fulfilled that which was spoken by Jeremy the

prophet, saying, In Rama was there a voice heard, lamentation,

and weeping, and great mourning, Rachel weeping for her

children, and would not be comforted, because they are not. Bethlehem was the burying place of Rachel, where Jacob marked her grave with a pillar after she died giving birth to Benjamin (Gen. 35:16-20; 48:7). Because Rachel was buried in Bethlehem, she is deemed its spiritual matriarch, and cries out for the children here. Rachel was also the mother of Joseph, whose children, Ephraim and Manasseh, were made tribes in Israel (Gen. 48:5, 6). |

Jacob associated the constitution of Ephraim and Manasseh as tribes in Israel with the death of Rachel (Gen. 48:7), as if God supplied through Joseph what Jacob might have realized in Rachel had she not died. Ephraim was among the northern tribes carried into captivity by the Assyrians. Jeremiah’s prophecy describes Rachel weeping for her children, because they were carried away captive. Despite the loss of her children, Rachel could take comfort in the captivity’s return and the resettlement of the land.

“Thus saith the Lord: A voice was heard in Raham, lamentation,

and bitter weeping; Rachel weeping for her children refused to be

comforted for her children, because they were not. Thus saith

the Lord; refrain thy voice from weeping, and thine eyes from

tears: for thy work shall be rewarded, saith the Lord; and they

shall come again from the land of the enemy. And there is hope

in thine end, saith the Lord, that thy children shall come again

to their own border.” Jer. 31:15-17

The return of the captivity, in

turn, anticipates the New Testament and coming of Christ: God

would bring again the captivity and make a new covenant with

Israel and Judah, first, in marrying again the bride he put away

by the captivity, but ultimately by the new covenant inaugurated

by the death of Jesus Christ (Jer. 31:27-34; Heb. 8:8-12). It is

this latter, plenior

sensus (fuller sense) of Jeremiah’s prophecy that Matthew

here affirms was fulfilled in the slaughter of Bethlehem’s

babes.

19 – But when Herod was dead,

Josephus tells us that Herod died in the seventieth year of his life,

“the fifth day after he had caused Antipater to be slain; having

reigned, since he had procured Antigonus to be slain thirty-four

years; but since he had been declared king by the Romans,

thirty-seven.”[34]

For many years the great majority of writers assumed Herod died in 4 B.C. However, the weight of current scholarship now holds that Herod died shortly before Passover 1 B.C. Evidence placing Herod’s death in 1 B.C., and where we may place the birth of Christ, may be seen in the following table, itemizing events in Roman history and the life of Herod

|

Year B.C. |

Event in Roman Empire/Life of Herod |

Antiquities of the Jews / Citation |

|

72 |

Herod born. |

XIV, ix, 2 |

|

63 |

Pompey the Great captures

Jerusalem Tishri 10. |

XIV, iv |

|

49 |

Julius Caesar makes war

against Roman senate and Pompey the Great. |

XIV, vii, 4 |

|

48 |

Pompey’s forces defeated

at battle of Pharsalus. |

|

|

48 |

Pompey killed in Egypt;

Caesar’s Alexandrian War. |

XIV, viii, 1, 2 |

|

47 |

Caesar makes Antipater,

father of Herod, procurator of Judea; Herod given charge

of Galilee at age 25. |

XIV, viii, 3, 4; ix, 2 |

|

44 |

Caesar assassinated; Marc

Antony and Octavian make war against Cassius and Brutus. |

|

|

42 |

Cassius and Brutus

defeated at Philippi. |

XIV, xii, 2 |

|

41 |

Marc Antony comes into

Asia; falls in love with Cleopatra; Herod and his

brother, Phasaelius made tetrarchs. |

XIV, xiii, 1 |

|

39 |

Parthians invade

Palestine; capture Phasaelius and Hyrcanus; install

Antigonus as king; Herod flees to Rome where he is made

king. |

XIV, xiii, 5-10; xiv,

1-5; |

|

38 |

First regnal year of

Herod; marches on Jerusalem; army goes into winter

quarters. |

XIV, xv, 1-3 |

|

37 |

Herod clears Galilee of

robbers and brigands; army goes into winter quarters a

second time. |

XIV, xv, 4 |

|

36 |

Herod captures Jerusalem

Tishri 10, 27 years to the day after Pompey took the

city; Antigonus executed by Antony, ending Hasmonean

dynasty 126 year after it began 162 B.C. Hyrcanus held

high priesthood 24 years from Pompey; Antigonus held if

3 years 3 months, or 27 years between them. |

XIV, xvi, 1-4; XX, x, 1 |

|

31 |

Battle of Actium

(September) occurs during Herod’s seventh year . This

would be the sixth year of Herod’s reign if capture of

Jerusalem dated to 36 B.C., but seventh according to

Josephus’ erroneous consular and Olympiad dates (37 B.C.). It

would also be the seventh if reckoned as Herod’s regnal

years from Tishri 38 B.C., having been made king in Rome

the winter of 39 B.C. |

XV, v,

2 |

|

30 |

Antony and Cleopatra die;

Herod well received by Octavian, who adds Gadara,

Hippos, and Samaria, and the maritime cities of Gaza,

Anthedon, Joppa, and Strato’s Tower to Herod’s kingdom. |

XV, vii, 3 |

|

26 |

In honor of title

“Augustus” given to Octavian by Roman senate January 27

B.C., Herod renames Samaria “Sebaste” and undertakes its

fortification and improvement. |

XV, viii, 5 |

|

26-25 |

There are two years of

famine beginning the 13th year of Herod’s

reign. |

XV, ix, 1 |

|

20 |

Augustus Caesar comes

into Syria during 18th year of Herod’s reign.

Herod undertakes rebuilding of temple in 18 year of his

reign (13th year per Wars, I, xxi. 1). |

XV, x, 3; XV, xi, 1 |

|

11 |

Caesarea Sebaste

completed in Herod’s 28th year in the 192d

Olympiad |

XVI, v, 1 |

|

2 |

Beginning of the 34th/37th

year of Herod’s reign; Augustus declared

“Pater Patriae”

by senate and people of Rome (Feb. 5); registration

under Saturninus (and Cyrenius); Antipater travels to

Rome where he remains seven months; Joseph and Mary

travel to Bethlehem; Jesus born 4th Quarter

December, 2 B.C. |

XVII, ii, 4; iii, 2; iv,

3 |

|

1

January |

Varus replaces Saturninus

as president of Syria; trial of Antipater before Herod

and Varus.

Herod falls into his last illness; makes new will; Jews

remove Roman eagle over temple gate; rabbis burned to

death; that night (Jan. 10th) there was a lunar eclipse. |

XVII, v; XVII, vi, 1-4 |

|

February

1st Quarter |

Jesus’ presentation at

temple (Feb. 2); offerings for Mary’s ritual impurity;

holy family returns to Nazareth. |

Lk. 2:22-24, 39 |

|

February

2nd Quarter |

Magi arrive in Jerusalem;

are sent to Bethlehem by Herod; star directs instead to

Nazareth; flight to Egypt. |

Matt. 2:1-13 |

|

February

3rd Quarter |

Herod leaves Jerusalem;

travels to mineral springs at Callirrhoe beyond the

Jordan River. |

XVII, vi, 5 |

|

March

2nd Quarter |

Herod returns to palace

at Jericho; orders principle men of Jews to be shut up

in Hippodrome and to be slain at his death. |

XVII, vi, 5 |

|

March

3rd Quarter |

Letters come from Caesar

giving Herod authority to execute Antipater; Herod

orders Antipater’s execution, Slaughter of the

Innocents; amends will, naming Archelaus king; dies five

days later. |

XVII, vii; viii, 1; Matt.

2:16-18 |

|

March

4th Quarter |

Herod’s funeral and

mourning; Archelaus provisionally assumes government,

pending confirmation of Herod’s will by Caesar. |

XVII, ix, 1-2 |

|

April

2nd Quarter |

Passover of the Jews

(April 8th); sedition of Jews over execution of rabbis

by Herod; 3,000 Jews slain by Archelaus in attempt to

suppress sedition. Archelaus and royal family sail to

Rome for confirmation of Herod’s will. |

XVII, ix, 3-7 |

|

June

|

Judea marked by tumults

and disturbances beginning at Pentecost, which are

quieted by Varus; Jews send ambassadors to Rome to

petition to live at liberty under their own laws, and

not under the government of Archelaus. |

XVII, x, 2-10; xi, 1, 2 |

|

July |

Caesar confirms Herod’s

will; makes Archelaus ethnarch of half of Herod’s

kingdom; the other half is divided between Herod Philip

and Herod Antipas. |

XVII, xi, 4 |

|

Aug.-Dec. |

Archelaus assumes

government of Judea; Holy family returns from Egypt,

turns aside to Nazareth. |

Matt. 2:19-23 |

We have placed Jesus’ birth in

the final quarter of December, 2 B.C. (the traditional date of

December 25th), as this seems to be recommended by the

chronology. We know the Magi had to arrive

after the holy family

returned to Nazareth about forty-five days following Jesus’

birth, but before Herod left Jerusalem and travelled to the

mineral springs at Callirrhoe beyond the Jordan River.

Therefore, assuming there

was no extended period between the return to Nazareth and the

arrival of the Magi, and the arrival the Magi and Herod’s

departure from Jerusalem, we should be able to reckon backward

from Passover following Herod’s death to his departure from

Jerusalem, and from there to find the date of the Nativity. Here

are the events as given by Josephus from Herod’s departure from

Jerusalem until Passover, 1 B.C., and the approximate time for

their accomplishment as given by Steinmann[35]:

|

Event |

Days Elapsed |

Total Minimum Days Elapsed |

|

Herod’s physicians tried

many remedies |

1 day minimum (more

likely 2-3 weeks) |

1 (more likely 14-21) |

|

Travel from Jericho to

Callirrhoe (about 50 miles) |

3 days minimum |

4 |

|

Treatment at Callirrhoe |

1day minimum (more likely

1 week or more) |

5 (more likely 11 or

more) |

|

Return to Jericho |

5 day minimum |

8 |

|

The Jewish elders

throughout Herod’s realm are summoned |

6 days minimum |

14 |

|

Herod receives permission

to execute Antipater and has him executed |

1 day minimum |

15 |

|

Herod’s death five days

later |

5 days |

20 |

|

Funeral arrangments and

funeral |

5 days minimum |

25 |

|

Seven days of mourning |

7 days |

32 |

|

Feast in Herod’s honor |

1 day |

33 |

|

Archelaus’ inintal

governance |

7 days |

40 |

|

The Passover |

1 day |

41 (more likely 62) |

Steinmann is mistaken in one

point of his chronology: Steinmann has Herod already at Jericho

when the rabbis are executed and leaves from there for the

mineral springs at Callirrhoe. (see footnote 26, above). This is

based upon a misreading of Josephus where he says that, when the

treatment at Callirrhoe failed, Herod returned to Jericho. But

this merely refers to Herod’s passing through Jericho on the way

to Callirrhoe, and does not indicate Herod originally set out

from there. Josephus is clear that Herod sent the rabbis to

Jericho for execution, showing Herod himself was not there.

Hence, Herod’s journey to the mineral springs at

Callirrhoe must have originated from Jerusalem shortly after the

arrival of the Magi.

Otherwise accepting Steinmann’s

numbers as good approximations, let us say that forty-one days

was the minimum period from Herod’s departure for Callirrhoe

until Passover, but sixty-two days as more likely. Using this

latter figure, then, we find that sixty-two days from Passover,

April 8th, brings us to February 5th. This would be the putative

date Herod departed from Jerusalem for the mineral springs. If

we then reckon backward three days (the period necessary for the

Holy Family to travel from Jerusalem to Nazareth), this would

bring us to February 2nd, the traditional date of the

Presentation of Christ at the temple. If we reckon backward

forty-days more (the period of ritual impurity before the

Presentation of Christ at the temple) we arrive exactly at

December 25th.

We are certain Steinmann did not intend this result or even realize the date of Christ’s birth lay before him this way. Steinmann was concerned solely with the chronology of Herod’s reign, and therefore never gave thought to carrying the chronology of Herod’s last illness and death backward to find the date of Jesus’ birth. But there it is all the same. The traditional date of Christ’s nativity is fully authenticated quite unintentionally by this noted scholar. And this result will not be greatly changed even if we use the minimum number of days Steinmann allotted. By allowing a short time between the holy family’s arrival at Nazareth before the Magi arrive, and between the Magi’s arrival and Herod’s quitting Jerusalem (as we have in our own table, above), the Nativity would still very probably fall on or near December 25th. The same result obtains based upon Luke’s and John’s chronology of Jesus’ baptism and first disciples.

Jewish law and convention

required that men be thirty years old before beginning active,

public teaching (Num. 4:3, 23). Luke says Jesus was on the

threshold of his thirtieth birthday (“began to be”) when he was

baptized by John in the River Jordan (Lk. 3:23). Jesus had a

three and a half year ministry beginning at his baptism and

ending with his crucifixion Good Friday, Nisan 15, A.D. 33. If

we reckon backward three and a half years (forty-two lunar

months, the Jews used a lunar calendar) from Jesus’ crucifixion,

that will bring us to Heshvan 15, A.D. 29., the fifteenth year

of Tiberius (Lk. 3:1) (A.D. 32 was a leap year of thirteen

months). Heshvan 15 that year translates into November 8th,

which thus becomes the date of Jesus’ baptism. Jesus then

underwent a period of fasting and temptation in preparation for

his ministry (Lk. 4:1-13). Since it is unlikely Jesus would

erect a barrier to his life’s work by an extended fast, we judge

that his fast and temptation were timed as to end upon his

thirtieth birthday, allowing him immediately to begin teaching

once these were out of the way. Jesus’ fast was forty days long.

That brings us to December 18th. If we allow one week

for the temptation, during which he hungered and was tempted to

turn stone into bread, then travelled to a high mountain and was

shown the kingdoms of the world, then to Jerusalem where he was

tempted to throw himself down from a pinnacle of the temple,

that would bring us to December 25th.

Following his fast and

temptation, Jesus returned to John the Baptist at Bethabara,

where he made his first disciples (Andrew, Peter, Phillip and

Nathaniel), showing he was now fully thirty years of age (Jn.

1:26-51). John enumerates seven days (Jn. 1:26, 29, 35, 43; 2:1)

beginning with Jesus’ return to John the Baptist and ending with

the wedding at Cana, where Jesus manifested (Gk.

efanerwsev)

his glory to his disciples by turning water into wine (Jn.

2:1-11). This first miracle is commemorated by the Feast of

Epiphany on January 6th. If we accept this date as

sound (it is mentioned by Clement of Alexandria A.D. 150- 215),

counting backward seven days, we find Jesus would have returned

to John December 31st, already having turned thirty

years old. Jesus’ thirtieth birthday therefore occurred sometime

in the fifty-three day window following his baptism before the

close of the year, most likely at the end of his fast and

temptation.

Thus, whether reckoned backward

from Passover following Herod’s last illness and death, or from

Jesus’ baptism and wilderness fast and temptation to making his

first disciples and the wedding at Cana, the final quarter of

December comes forward as the most likely date of Jesus’ birth.

[36]

behold, an angel of the Lord appeareth in a dream to Joseph in

Egypt, saying, Arise, and take the young child and his mother,

and go into the land of Israel: for they are dead which sought

the young child’s life.

Herod died within about one month

of the holy family’s flight to Egypt. However, it would be

several months before Caesar confirmed Herod’s will and the

government of Judea was settled upon Archelaus. Based upon v.

22, the holy family did not return immediately upon the death of

Herod, but after Archelaus had assumed the government of Judea.

21, 22 – And he arose, and took the young child and his mother,

and came into the land of Israel. But when he heard that

Archelaus did reign in Judaea in the room of his father Herod,

he was afraid to go thither: notwithstanding, being warned of

God in a dream, he turned aside into the parts of Galilee.

“Though the serpent is dead, one of his brood doth reign in his stead.” At Herod’s death, the sons of Herod and the rest of the royal family sailed to Rome, where the parties disputed who should reign in place of Herod. Following the conviction of Antipater, Herod changed his will, naming Herod Antipas heir of his kingdom, but after Antipater’s execution, he changed his will and made Antipas tetrarch of Galilee and Berea, but granted the kingdom to Archelaus, making Philip tetrarch of Gaulonitis and Trachonitis, and Paneas.[37] Caesar confirmed Herod’s will with modification:

“When Caesar had heard these pleadings, he dissolved the

assembly; but a few days afterwards he appointed Archelaus, not

indeed to be king of the whole country, but ethnarch of one half

of that whcich had been subject to Herod, and promised to give

him the royal dignity hereafter, if he governed that part

virtuously. But as for the other half, he divided it into two

parts, and gave it to two other of Herod’s sons, to Philip and

to Antipas.”[38]

Ten years later, Archelaus was

banished to Vienna, a city of Gaul, for his cruel and tyrannical

rule over the Jews, proving that he was the true son of his

father. Heaven thus warns Joseph to turn aside to Galilee, which

is beyond Archelaus’ jurisdiction, belonging instead to Herod

Antipas, to whom Pilate sent Jesus at his trial (Lk. 23:7).

23 – And he came and dwelt in a city called Nazareth: that it

might be fulfilled which was spoke by the prophets, He shall be

called a Nazarene.

Nazareth had been the holy family’s home from the start; they now return to it where they will remain until Jesus begins his ministry when he reaches thirty years of age. There is no recorded prophecy that the Christ would be from the city of Nazareth. Rather, the sense seems to be that the prophets spoke of Christ by some term belonging to the same root, such that, in dwelling at Nazareth, Jesus bore the name thus foretold. The root of “Nazareth” and “Nazarene” is the Hebrew “ntsr,” or “netzer,” “a branch,” which term Isaiah used of Christ:

“And there shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse, and

a Branch shall grow out of his roots.” Isa. 11:1

Another possibility is the term

“Nazarite,” meaning “separated,” from the vow of consecration

established by Moses (Num. 6). The similarity of the term

“Nazarite” with “Nararene,” although of a slightly different

root (“nzr”), seems to anticipate Christ, who, though not a

Nazarite proper, nevertheless was so set apart and consecrated

to God that the prophetic type might find fulfillment in him. In

short, both of these terms appear to have been set by Divine

arrangement in sacred literature with a view to the name that

would be called upon Christ. Pilate thus wrote the accusation

that hung upon the cross of Christ: “Jesus of Nazareth, King of

the Jews” (Jn. 19:19); this title still appears today on

crucifixes and images of the cross in Latin abbreviation by the

letters “INRI” – “Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum.”

[1]

Josephus, Antiquities, XVII, I, 1; Whiston ed.

[2]

Josephus, Antiquities, XVII, ii, 4; Whiston ed.

[3]

Tertullian, Against Marcion, IV, xix; Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. 3, p. 378; cf.

Justin Martyr,

Apology, 1, xxxiv, xlvi;

Dialogue with

Trypho, 78.

[4]

See generally, Jack Finegan,

Handbook of

Biblical Chronology, Revised ed. (Hendrickson,

1998), pp. 302-306;

F.W. Farrar, The

Gospel According to St. Luke, (Cambridge, 1882), pp.

62-64.

[5]

As quoted in Finegan, p. 306.

[6]

Josephus, Antiquities, XVIII, vi, 10.

[7]

Josephus, Antiquities, XIX, v, 1.

[8]

Josephus, Antiquities, XIX, viii, 2.

[9]

Josephus, Antiquities, XIX, v, 1; ix, 1-2; XX, i, 1;

v, 2; vii, 3;

Wars, II, xii, 1

[10]

Josephus, Wars, III, iv, 2; V, i, 5.

[11]

Suetonius, Titus, VIII. Dio Cassius, LXV, xv, 4; LXVI, viii, 1. For Josephus’

account of the posterity of Herod the Great, see

Antiquities, XVIII, v, 4

[12]

I Macc. 13:41, 42.

[13]

Josephus, Antiquities, XIV, i-ix, 2.

[14]

Josephus, Antiquities, XIV, xii-xiv, 5. Josephus’ Olympiad dates do not agree

with his consular dates. The one hundred eighty-fourth

Olympiad ended June 30, 40 B.C., but Calvinus and Pollio

were not made consuls until after the Treaty of

Brundisium on October 2, 40 B.C. Hence, it is probable

that Herod received his appointment in December 40 B.C.,

during the one hundred eighty-fifth Olympiad. (See

Ormond Edwards, “Herodian Chronology”

PEQ 114 (1982) 29-42, p. 30; Andrew E. Steinman, “When Did Herod

Reign” Novum

Testamentum 51 (2009) 1-29, p. 7).

[15]

Appian, Civil Wars, 5.8.75. Sections 69-76 cover the years 39 B.C. as may be

seen by comparison with Dio Cassius’

Roman History.

[16]

Josephus, Antiquities, XIV, xvi, 4. The period of twenty-seven years is

corroborated by the time Hyrcanus served as high priest

from appointment by Pompey, which Josephus gives as 24

years, plus three years and three months the office was

held by Antigonus.

Antiquities, XX, x,

1.

[17]

Dio Cassius,

Roman History

49.23.1-2.

[18]

Josephus, Antiquities, XIV, xvi, 4; XX, x, 1.

Steinman, When Did

Herod Reign, p. 9.

[19]

Josephus, Antiquities, XX, x, 1; Whiston ed.

[20]

Herodotus, 100, 107.

[21]

The rulers of the Jews knew and understood Aramaic when

speaking with the Assyrians ambassadors (II Kng. 18:26).

[22]

Johannes Kelper, De anno

natali Christi

(1614). Earnest L. Martin,

The Star that

Astonished the World (ASK Publications, 1996); Craig

Chester, President, Monterey Institute for Research in

Astronomy, The Star of Bethlehem, IMPRIMIS

(Hillsdale College) December 1993; John Mosley,

Program Supervisor, Griffith Observatory, Common

Errors in "Star of Bethlehem" Planetarium Shows, The

Planetarian, Third Quarter 1981.

[23]

Josephus, Antiquities, XV, x, 4; Whiston ed.

[24]

Josephus, Antiquities, XVII, v-vi, 4.

[25]

W. E. Filmer, The

Chronology of the Reign of Herod the Great, JTS 17

(1966), pp. 283-298; Earnest L. Martin,

The Birth of Christ Recalculated (Pasadena: Foundation for Biblical

Research, 1978); idem

The Nativity and

Herod’s Death, CKC 85-92; idem,

The Star that

Astonished the World (2nd ed.; Portland:

ASK Publications, 1996); Jack Finegan,

Handbook of

Biblical Chronology (Revised ed.;

Hendrickson, 1998); Andrew E. Steinmann,

When Did Herod the Great Reign?, Novum Testamentum 51 (2009), pp.

1-29.

[26]

Steinmann is mistaken here, in that he has

Herod already at Jericho when the rabbis are executed

and leaves from there for the mineral springs at

Callirrhoe; but Josephus is clear that Herod

sent the

rabbis to Jericho for execution, showing Herod himself

was not there. The better view is that Magi found Herod

still at Jerusalem shortly after the rabbis’ execution;

Herod then left for Callirrhoe shortly thereafter.

Steinmann, When

Did Herod the Great Reign?, p. 13

[27]

The traditional names Melchior, Caspar, and Belthazar

are thought to derive from a Greek manuscript dated to

about A.D. 500, translated into a Latin document

entitled Excerpta Latina Barbari. “At that time

in the reign of Augustus, on 1st January the Magi

brought him gifts and worshipped him. The names of the

Magi were Bithisarea, Melichior and Gathaspa." Ibid at

p. 51.

[28]

Josephus, Antiquities, XIV, VII, 2; XIV, x, 1, 2.

[29]

“Herod…is best known as the sly and murderous monarch of

Matthew's Gospel, who slaughtered every male infant in

Bethlehem in an unsuccessful attempt to kill the newborn

Jesus… Herod is almost certainly innocent of this crime,

of which there is no report apart from Matthew's

account..” Tom Mueller,

King Herod

Revealed, National Geographic (December 2008) p. 42.

Cf. Rev.

Masson, A Vindication of the Defense of Christianity Vol. II,

The Slaughter of

the Children of Bethlehem, as an Historical Fact of St.

Matthew’s Gospel, Vindicated, (London, 1728).

[30]

Josephus, Antiquities, XVI, vii, 1; Whiston ed.

[31]

Suetonius, Augustus, XCIV, 3; Loeb ed.

[32]

Josephus, Antiquities, XVII, vi, 5; cf.

XV, 1-10.

[33]

Macrobius, Saturnalia, II, 11; Loeb ed.

[34]

Josephus, Antiquities, XVII, viii, 1; Whiston ed.

[35]

Steinmann, When Did Herod the Great Reign?, p. 15, 16. For a copy of Steimann’s

piece, go to

http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/brill/not/2009/00000051/00000001/art00001

[36]

For a fuller treatment of the date of Christ’s birth,

see the author’s article

“Unto You is Born

this Day: The Biblical Case for the December 25th

Birth of Christ”

www.dec25th.info. See also, the author’s

Tables of Priestly

Courses from 23 B.C. to A.D. 70, demonstrating the

validity of the traditional date based upon Zechariah’s

ministration in the temple.

[37]

Josephus, Antiquities, XVII, vi, 1; viii, 1.

[38]

Josephus, Antiquities, XVII, xi, 4; Whiston ed.

______________________________

Adoration of the Shepherds

All rights reserved.

John Seleden’s

John Seleden’s